…in a mirror, darkly…

für Violine, Cello und Klavier (2023)

UA: 09.06.2024 Haus Welbergen, Ochtrup, Ensemble Sinfonia

(7min)

Information

Nationalhymnen sind ein nicht immer einfaches Zeugnis der Geschichte eines Landes. Sie können historisch belastet sein oder unter völlig anderen gesellschaftlichen Umständen entstanden sein, die einem heute fremd sind. Häufig erzählen sie vom Ringen um Frieden und Souveränität, viele haben einen militärischen Gestus, kraftvoll, auftrumpfend. Die französische Nationalhymne, die Marseillaise, ist ein besonders drastisches Beispiel für einen solchen Text, entstanden während der französischen Revolution zur Mobilisierung des Volkes gegen eine als ungerecht empfundene Herrschafts- und Gesellschaftsordnung. Und obwohl das Anliegen der Revolutionäre gut und wichtig war, wird man den im Lied besungenen Blutdurst einseitig und wenig aufgeklärt finden müssen. In Zeiten komplizierter, vielschichtiger Konflikte jedenfalls kann eine solche Geisteshaltung nichts zu einer friedlichen, vernunftgesteuerten Problemlösung beitragen. Diese Komposition ist anlässlich eines Konzertes zum Thema Frieden entstanden, während am Rand von Europa der Ukrainekrieg tobt. Sie ist als persönlicher Kommentar zu verstehen: Kriege sind immer Tiefpunkte der Menschheit, das Töten von Menschen verdient keine heroischen Lieder. Das Anliegen der Komposition ist es daher, die Marseillaise musikalisch in ihrer ganzen Zerrissenheit zu zeigen, ihr die militärischen Flügel zu stutzen und ihr die Komplexität des Krieges, den sie besingt, zurückzugeben. Der Titel des Stück, ein Zitat aus dem Buch Kohelet, beschreibt das kompositorische Prinzip des Stückes: die eingängige Melodie der Marseillaise verschwindet hinter einem trüben Schleier, verliert ihr Marschcharakter und ist nun eingebettet in zarte Klanggesten. Die Töne der Melodie sind dabei fast durchgehend Grundlage für die Motive der Komposition, auch wenn es nicht immer hörbar wird.

Im Zentrum der Komposition steht der Gedanke, den Charakter der Marseillaise zu "brechen", also den triumphalen Marschcharakter zu (zer)stören.

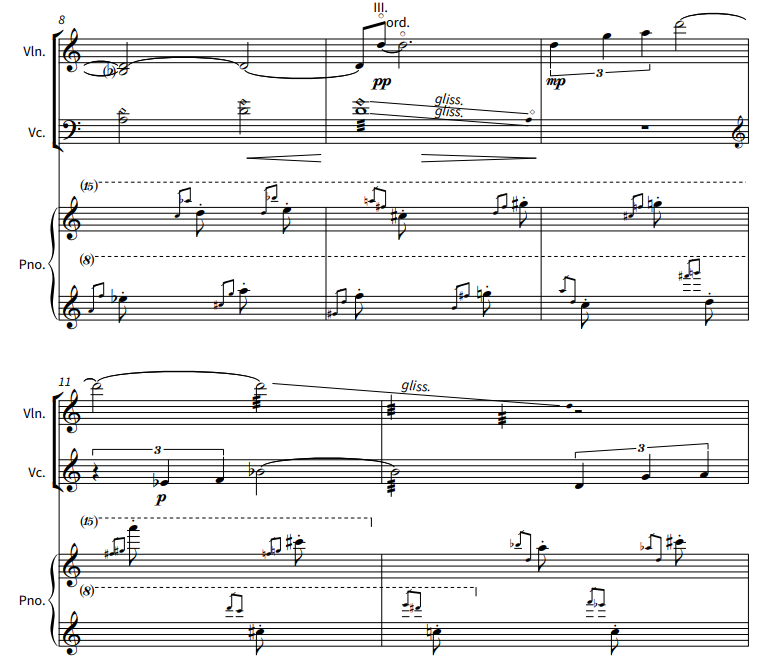

Der erste Satz integriert zwei charakteristische musikalische Merkmale der Marseillaise: Die aufsteigende Tonfolge aus 4 Tönen am Anfang (Grundton, Quarte, Quinte, Oktave) und den markanten punktierten Rhythmus der ersten drei Töne. Beide Elemente werden nur getrennt voneinander benutzt (d.h. die Ton mit anderem Rhythmus und der originale Rhyhtmus nur auf einer Tonhöhe). Im ersten Satz wird die besagte Tonfolge zwischen Violine und Cello wie ein Faden zu einem lockeren Gewebe gestrickt, während das Klavier nervöse kleine Figuren spielt. Die Melodie soll zart wirken, mit einer dennoch unterschwelligen Bedrohlichkeit. Irgendwann stürzt der Klang förmlich in die Tiefe, der punktierte Rhythmus taucht hier und da auf, bis der Satz leise und dunkel verklingt.

Der zweite Satz ist eine Art freie Improvisation des Klaviers, wo die Streicher nur wenige Klänge ergänzen. Man den Anfang der Marseillaise und einzelne Melodiefetzen, nachdenklich und verträumt.

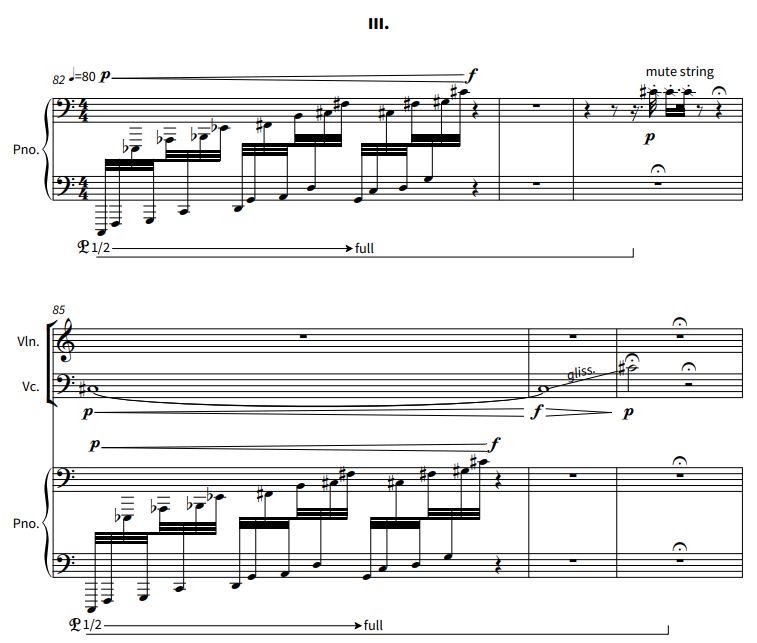

Der dritte Satz beginnt mit einem aus der Tiefe emporsteigenden Grollen, auch dieses ist den Anfangstönen und Intervallen der Marsaillaise entnommen, auch wenn es kaum hörbar ist. Im späteren Verlauf kehrt auch der pulsierende Rhythmus wieder, durch das Dämpfen der Klaviersaiten klingt es sehr metallisch und erinnert damit vor allem an die Maschinenästhetik von Krieg.

National anthems are not always a simple testimony to a country's history. They can be historically charged or have been created under completely different social circumstances that are unfamiliar today. They often tell of the struggle for peace and sovereignty, many have a military gesture, powerful and defiant. The French national anthem, the Marseillaise, is a particularly drastic example of such a text, written during the French Revolution to mobilize the people against a ruling and social order that was perceived as unjust. And although the revolutionaries' cause was good and important, the thirst for blood sung about in the song must be seen as one-sided and unenlightened. At any rate, in times of complicated, multi-layered conflicts, such a mindset can contribute nothing to a peaceful, reason-driven solution to problems. This composition was written on the occasion of a concert on the theme of peace, while the war in Ukraine is raging on the outskirts of Europe. It is to be understood as a personal commentary: Wars are always low points of humanity, the killing of people does not deserve heroic songs. The aim of the composition is therefore to show the Marseillaise musically in all its conflicting aspects, to clip its military wings and give it back the complexity of the war it sings about. The title of the piece, a quotation from the Book of Kohelet, describes the compositional principle of the piece: the catchy melody of the Marseillaise disappears behind a murky veil, loses its marching character and is now embedded in delicate sound gestures. The notes of the melody are the basis for the motifs of the composition almost throughout, even if this is not always audible.

The first movement integrates two characteristic musical features of the Marseillaise: The ascending sequence of 4 notes at the beginning (root, fourth, fifth, octave) and the distinctive dotted rhythm of the first three notes. Both elements are only used separately (i.e. the notes with a different rhythm and the original rhythm only on one pitch). In the beginning, the aforementioned sequence of notes between violin and cello is knitted like a thread into a loose fabric, while the piano plays nervous little figures. The melody is intended to appear delicate, yet with an underlying menace. At some point, the sound literally plunges into the depths, the dotted rhythm appears here and there until the movement fades away quietly and darkly.

The second movement is a kind of free improvisation by the piano, where the strings only add a few sounds. One hears the beginning of the Marseillaise and individual melodic fragments, pensive and dreamy.

The third movement begins with a rumble rising from the depths, which is also taken from the opening notes and intervals of the Marsaillaise, even if it is barely audible. Later on, the pulsating rhythm returns; the muffling of the piano strings makes it sound very metallic and is therefore particularly reminiscent of the machine aesthetic of war.